I have decided to post Chapter 10 in its entirety – I didn’t know what to leave out and I found this to be a delightful Chapter.

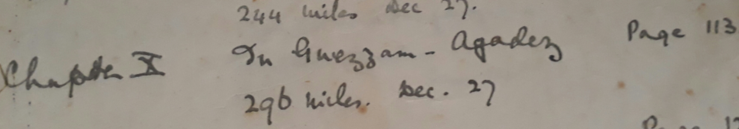

“The position was that we were due to leave In Guezzan at 12.30 and we actually left at 2.16, so we were 1 hour and 46 minutes behind schedule. We had spent 28 minutes at In Guezzam. I allowed half an hour so I need not have been so needlessly enraged at the delay! We were now starting on the 290 miles stage to Agadez, and this marks the end of the desert crossing proper; we felt that we were quite near our primary objective, Kano. Actually it was 750 miles away and we reckoned such distances seemed quite close and anyway we knew that the worst part of the crossing was over.

The track from In Guezzan to In Abbangarit, of which the latter consists quite simply of a well and nothing else, is the part of the Hoggar crossing which is most subject to sandstorms and we were quite prepared, in view of the appalling conditions we had met with thus far, to be involved in one of these pests of the desert at any moment. So liable is this part of the track to be swept by sandstorms, that the cairns marking the track here are replaced by iron stakes with the flags, exactly like those to be seen on the greens on a golf course. The track is perfectly flat, nothing but a bare expanse of sand with, here and there, dunes of sand rising from its surface; though the lines of flagged stakes stretching away into the distant are easy to follow. It is not an easy track to make good speed on, because patches of really deep sand abound and these are cut into deep ruts by passing vehicles. One would be travelling at a comfortable 50 mph on smooth sand, when suddenly the appearance of the surface changes to a kind of greyish colour, the wheels would sink and one’s speed would fall off immediately: then one would make a lightening change to second and stamp on the accelerator, up to third again and the engine speed rising, and then perhaps quickly down to second again for another deep patch. And so on. Always ready to swerve away to right or left sometimes half a mile or more from the line of flags to avoid stretches of deeply rutted track. Occasionally one found that these detours lead one in all sorts of difficulty; I remember that once Humfrey, going off on a line of his own, became embroiled with a lot of sand dunes which are of course if not exactly unclimbable, at any rate not conducive to ease of mind: having arrived in a neighbourhood where we appear to be completely surrounded by these unattractive objects he had, most abjectly, to make a complete circle and return on his tracks to where he would strike off in a new direction. This to the accompaniment of irate remarks from me about people who know better than the Trans-Sahara white marker! This sort of criticism he always took with a cheerful grin, as I may say, did I when the occasion arose for him to make the same sort of commentary on the course I had chosen!

However, we progressed pretty well and were quite satisfied with the progress when In Abbanjait drew near. This, as I said, consisted of a well and nothing else but suddenly a surprising spectacle was presented to our astonished eyes. At first we simply could not make out what these objects were that loomed up above the horizon in the light of the setting sun, but as we approached, we became convinced that we were suffering from hallucinations. No, we weren’t though by Jove, these objects were tents, large lordly European tents not the ramshackle tents of the Negro or the black camel Lais tents of the Tuareg, but real proper white canvas tents. Two of them, and near them cars and lorries. Intrigued by the spectacle we slowed down and were hailed as we stopped to look at them. Two white men approached the car, quite unmistakably Englishmen, and one of them said “Hello, are you Symons, by any chance?” Humfrey admitted that he was and a stranger went on, “I’m Colonel ___ (I am afraid I’ve forgotten his name) and we were told at Kano that you were expected.” He went on to ask how long we had been, what sort of journey we had and how pleased he was to have met us. Then he called to the black servants and asked what we would have to drink but, the devil of urgency seizing us, we explained that we were sorry but we were most anxious to get on. He accepted our apologies and called out “Cheerio and good luck” as we sped off again across the desert. In spite of our missed drink the little encounter had cheered as up. They were so thoroughly, sweetly British with clean shaven chins and immaculate clothes, their tents, their deck-chairs, their servants, their keen interested welcome, even their prompt offer of “Have a drink?”, that it makes one feel as though, after crossing this vast expand of French territory, one was indeed approaching Britain across the seas: and it heartened us for the long journey still ahead of us. We had done, and were still doing well; we had made a substantial gain of time since we left In Guezzam; we were well ahead of record time, and perhaps our luck was going to change and Africa give us a warmer welcome than it had vouchsafed up to date. It was. After darkness fell, suddenly with a bang as it does in the tropics, we rushed through the cool evening air, very grateful after the blazing heat of the day, with our Lucas lamps throwing a great path of brilliant light far ahead; the track was hard and good, smooth baked earth and we were cheered, too, by the appearance of vegetation, coarse grass, bushes, even trees. These were welcome sights after the barren emptiness of the great Sahara, now dropping behind with every revolution of our good engine. We were at the place which our log called “Teggeda Tecum” which Humfrey swears is a town but of which I have never seen any sign except a T turning off the straight track with a dirty piece of board on which is scrawled the word ‘Agadez’ with an arrow pointing down the left-hand track. We turned down this and sped on, our speed rarely dropping much below 50 mph though we did not consider it advisable to drive faster in case we came suddenly on some gully across the track. It was on this part of the track that, on the occasion of our record run to Kano two years before in the Rolls-Royce, we lost two hours, and pretty grim two hours they were. But that is another story. On this occasion there was no getting lost and in what seemed an amazingly short time, the imposing tower of the mosque of Agadez rose up against the black starlight sky and we were running quietly into this considerable town. There is a French garrison here, a hotel, and a large native population. The inhabitants are Seuussi who were stirred up by the German agents during the war to revolt against the French and they gave a lot of trouble before they were defeated. The palace of the Senussi chieftain is now the hotel, to whose hospitable portals we now directed our course. As we drove up to the entrance, the manager, a Frenchman of course, ran out to meet us, “Monsieur Symons?” he queried “Ah Mr Symons,” he went on when informed “I was expecting you some hours ago, but I have heard nothing from In Guezzam (as usual, we had beaten the depannage telegram) nevertheless, everything is prepared if you will come this way.” He pointed us round to the side of the hotel when we saw six or seven Arab boys, cans of petrol, cans of oil, cans of water, funnels of various shapes and sizes “But how did you know exactly when we were coming?” we asked, surprised and delighted at his display of efficient organisation.

“Ah, Messieurs,” he exclaimed. “I was told to expect you at 6.50 and since then I have had a boy stationed on the top of the hotel to watch your lights. He had seen them coming for the last hour, so all is prepared.” French efficiency at its best!

Like lightning the petrol tank was full and, as we were rather dubious of being able to cover the 465 miles to Kano on our tank capacity of 31 gallons we took on board as precautionary measure a spare 4 gallon can. Although we had intended to go straight on and eat something as we travelled we were so impressed with the efficient arrangements made by the hotel manager that is we decided to have a meal here, feeling quite sure that it would be served promptly. We therefore asked him if we could have something to eat quickly. “Assurement Messieurs,” he replied, as if being asked to supply dinner to unexpected travellers at 10.30 at night was a perfectly normal procedure, “it’ll be ready in one little minute.” Before we went in, we put down the bed in the car as I, whose turn it was to be off duty, intended to sleep when we restarted. And went inside, into the lofty vaulted room with the carved Moorish columns meeting in an arch high above our heads, clean and white in the brilliance of the electric bulbs, for Agadez has its own town electricity supply. Hot water and cleaned towels were produced and, pulling off shirts, we indulged in the first wash we had had since we left Arak 1300 miles back in the heart of the desert. It felt good to be clean again, even if we did not waste time by shaving our three days growth of beard (fortunately both of us are fair, so we do not look quite so disreputable when unshaven as dark men do). We sat down at the cleaned, washed wooden table and prepared to enjoy our meal, and a good meal it was, though I do not remember of what it was comprised. We had bought in with us from the car a couple of half bottles of champagne, part of the store we had bought from England, as we felt that a little jollification would do us no harm and we deserved it after having crossed the desert faster than it had ever been crossed before.

As we sat, enjoying our meal and the champagne (this was decidedly warm but very comforting!) we studied the log, as we were entitled to consider that the main difficulty of the journey from Algiers to Kano was now over. We knew all about the track on from Agadez and though the first 100 miles or so would not be easy going, it was child’s play compared to what we had been through already. We were due at Agadez at 9.20 and we had actually arrived at 10.21, so were only one hour behind schedule. Our schedule time from In Guezzam to Agadez was 8 hours 50 minutes: so we had gained 45 minutes: we had actually average 36 1/2 mph for the 296 miles: after darkness fell we had averaged a fraction under 40 mph from In Abbanjait.

Once again I should like to point out that the ordinary traveler, driving an ordinary car, and the ordinary tourist could not hope to equal these speeds: and would do very well if he averaged 25 mph over this stretch. Our huge tyres and the superlative springing of the Wolseley, the careful weight distribution to which we had given an immense amount of thought, coupled with the fact that we are both expert long-distance drivers and experienced desert travellers, alone made such speeds possible. A commentary on the kind of travelling that a record breaker has to accomplish. I may say here that we left Arak at 9:05 p.m. and we arrived at Agadez at 11:40 p.m. the next night. We had covered 794 miles in these 26 ½ hours and our only stops had been 12 minutes at Tamaurasset and 28 minutes at In Guezzam, 40 minutes in all. Note that in 794 miles and, with the exception of the last 170 miles, this was over the most difficult part of the crossing!

That fact, which we had elucidated from the log book, meant that, provided we did not make abject asses of ourselves during the next 100 miles or so, either by losing our way or sticking in the sand; we had the Algiers – Kano record, our objective number one, in our pockets. Humfrey wrote out another cable for Thomas which the manager promised to dispatch in the morning, we paid our bill and were just preparing to leave when an unexpected and wholly delightful interlude occurred. Seated at a large table was a party of ten or twelve French officers, obviously from the garrison of Agadez: these officers had changed from their service uniforms and were now taking their ease in the short jacket and the loose baggy trousers of the Arab. We had of course greeted and been greeted by them when we came in; they had, with the true courtesy of the race, left us in peace to consume our dinner. Now, as we prepared to leave, the man who had been sitting at the head of the table rose and came across to us. He was a magnificent figure of a man, well over six feet, straight as a ramrod and lithe as a deer: young and exceedingly handsome, with dark wavy hair and bold dark eyes, he was very picture of a dashing French officer with all the fire and elan of his race, a splendid type, the ideal lean saber. In his right eye, he wore (of all things) a monocle and this completed the picture: he was an Onida guardsman come to life. He made a graceful bow to us, “Messieurs,” he said, “we have been told what you have done. Your performance in driving your car from Algiers to Agadez in 2½ days is altogether ‘formidable’. My companions and I will consider ourselves honored if you will take wine with us in celebration of your magnificent achievement.” What could we say? We were anxious to be on the road again but in the face of this handsome gesture, what was there for us to do? Humfrey, who speaks French like a native, replied that we should be only too delighted to comply with the invitation, and that we felt highly honored that our performance had met with their approbation. We moved over to their table, where room was made for us and bottles of champagne made a miraculous appearance. They were experienced desert travellers and discussed eagerly with us technical details of our journey; while our bold, laughing cavalier seized each bottle of champagne by the neck as it was emptied, and with a dexterous twist of the wrist sent it flying across the paved floor where it halted, unbroken to rest in a corner. This was evidently his star performance and never failed to arouse a huge applause from his boisterous companions. They were a grand, cheery crowd, perfectly sober, but brimming with high spirits, and the terrific, almost overpowering, personality of the handsome leader – whom they called “mon Capitaine” – made the whole scene almost too good to be true.

At last Humfrey remembered that we really must be going, and instantly they all rose to their feet, drank one last toast to our continued good fortune and trooped out to see us off. They were most interested in our Wolseley and they pronounced our huge tyres and our bed in the car, ‘tries practique’. We were proud of our good Wolseley when Humfrey pressed the starter and the engines sprang to life, murmuring its quiet song and murmuring as sweetly and silently as when we had left England 3000 miles back. A roar of cheers broke from the French officers and Humfrey let in the clutch and we slid off into the darkness on the last 460 mile lap of our journey to Kano.”

Up until now I have been editing and condensing each chapter. In this chapter I have decided to release it in it’s original format to give readers an idea of the detail that Bertie put into every moment of their epic journey.

Up until now I have been editing and condensing each chapter. In this chapter I have decided to release it in it’s original format to give readers an idea of the detail that Bertie put into every moment of their epic journey.

![IMG_3662[1]](https://thecaperecord.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/img_36621.jpg?w=739&h=554)

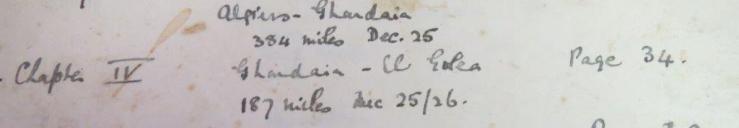

Ghardaia – El Golea

Ghardaia – El Golea