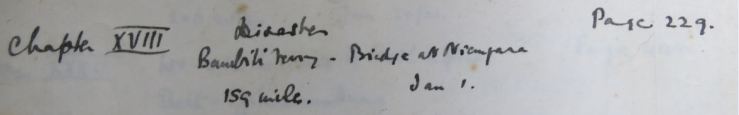

The night was short, thank Goodness. It must have been two o’clock before we were bathed, bandaged and left alone. And at six daylight stole into the quiet white room. Soon after, the sister, clean and cool in her white robes, came in with tea and Humfrey woke. We took stock of our wounds. Humfrey’s face was covered with small scratches, probably from flying glass, and his finger was painful. My left leg had five or six deep wounds on the front and side of the shin bone and we were both badly cut about the arms. Otherwise we were unhurt, though we felt stiff and bruised. While we were washing with some difficulty, owing to our bandages, I was able to shave though Humfrey was not, owing to the cuts on his face, the sister came along to tell us a man was here from the store. She had sent for him to bring a selection of garments, as of course our own were still wet through. This is another instance of the thoughtful kindness that we met with at Niangara, instances multiplies a hundredfold in the days to come. We made a selection, trying excellent solar topees for the sum of one and nine pence each. Of course, we had no money, as it was all in the car but the trader, who had worked in London and spoke excellent English, made no bones about that. Breakfast was bought to us in a pleasant room with wide verandahs on three sides and a cool morning breeze blowing in at the open French windows. I could eat nothing but Humfrey made an excellent meal. He got quite cross with me because I would only sit and mope with my head buried in my hands. He said we were lucky to be alive and was, almost exactly, his usual cheerful self. Wonderful fellow!

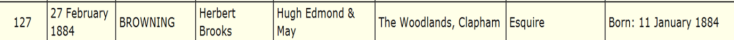

While we were still at breakfast, a car drove up. The doctor, a cheerful young Belgian, examined our injuries and re-bandaged them. Before he had finished more cars arrived. The Administrator – the big man of the district – the Chief of Police, a hearty young fellow, full of optimism, and the Bishop, a marvellous little man with a grey pointed beard, very neat and dapper in his white robes and the gold cross hanging on his breast. These four held an inquisition as we sat in that pleasant airy room and were amazed to hear that we were unhurt after our terrific fall. Then the Chief of Police, Loerand by name, said lightly “Well, Mr Symons, now you will want to get your car out of the river?”

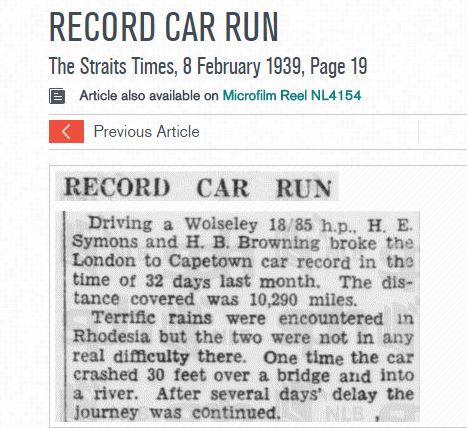

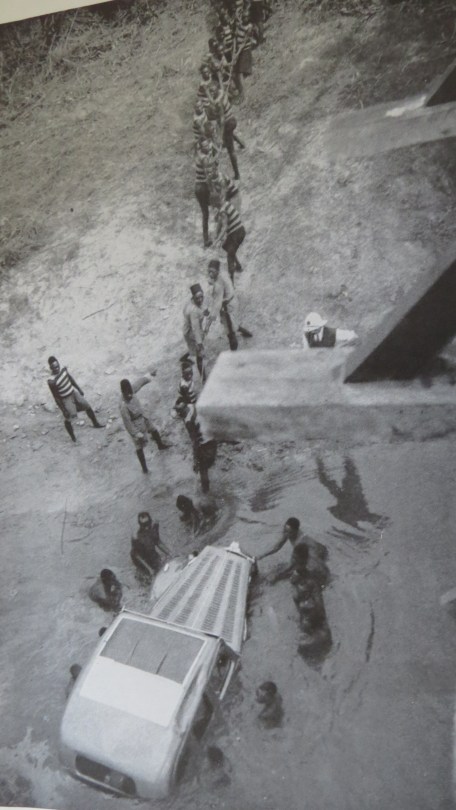

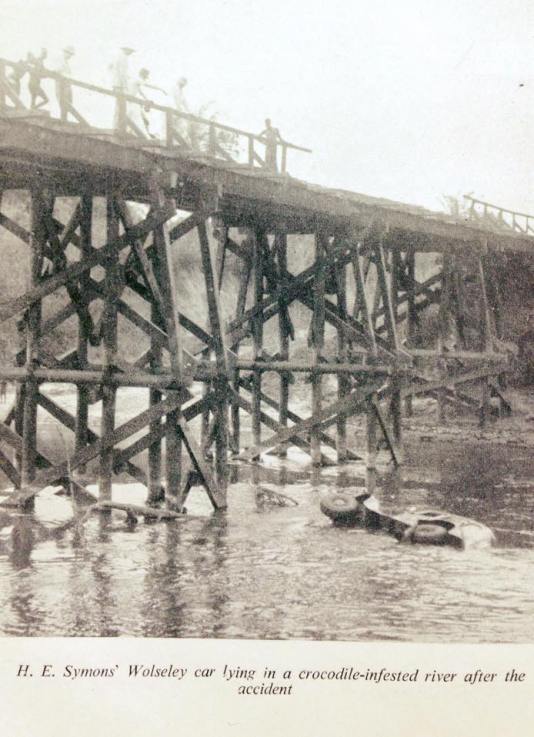

Symons said that he feared that would be impossible. Loerand replied “Nothing is impossible if one has enough men! I have already sent 50 prisoners to the bridge. I shall turn out two villages to help, and if that is not enough, I shall turn out two more.” We were still dubious. It seemed to us impossible that there could be anything left of the car after its fearful fall and its long immersion. But we agreed to go with them. Before we went, Humfrey borrowed from the sister her camera and some film as our own camera being of course submerged in the car. The Bishop drove us in his own Chevrolet, the other cars following. On the way we passed the 50 prisoners, in their uniform of black and yellow striped jerseys and blue shorts, marching towards the bridge. We arrived at the bridge. There, far below, lay our poor Wolseley on its side. Perhaps eight inches or so of the body with the open window through which we had climbed to safety above the swift water, and, as we looked down on it from the dizzy height of the bridge, it seemed impossible that we could have survived that ghastly fall. I remember distinctly the Administrator saying “Messieurs, veritably you have the good luck to still be alive.” We agreed. Loerand, the indefatigable chief of Police, would not hear of our doing anything, “No, no, you must be exhausted,” he said. “Leave it to me to arrange everything.”

He sent a party away somewhere down the river to bring a dug-out canoe and meanwhile those prisoners who could swim stripped off their clothes and swam out to the car which was lying exactly in the middle of the river. Loerand called out something to one of the prisoners, who thereupon held his arm straight up above his head and let himself sink to the bottom. When he was standing on the bottom his up stretched hand was 4 feet below the surface. So, he continued to take soundings till it was discovered that, although the water was only about 5 feet deep on each side. It was clear that we had fallen exactly on a sandbank in the middle of the river. If we had fallen 3 feet to the right or the left, our car would have been in eight feet of water and would have been completely submerged. In that case we should never have got out alive. While we were waiting for the dug-out canoe to arrive, we all walked across the bridge to try and re-construct exactly what had happened. No other vehicle had passed, and the track of our car was plainly to be seen on the sandy road. We saw the straight line it had taken after rounding the bend 200 yards away; then the line deviated to the right as the car had swerved under the application of the brakes. Standing on this line and facing towards the river, we could see how the track was pointing towards the abyss of the high embankment, with the entrance to the bridge away to the left. This coincided with my recollections. I remember seeing nothing but a black drop in front of me and swinging the car towards the bridge. The track showed this. It was a perfectly smooth curve. A straight line, an outward curve to the right, an inward curve to the left, and this inward curve led on to the bridge at a slight angle. We could see a mark where the near side front wheel had struck the guarding baulk of timber and at the same point the outer guard rail was smashed away. About 20 yards further on along the bridge we could actually see a slight abrasion on the timber where the huge tyre had climbed on the baulk (although it had been rubbing along it, the soft flexible tread had given it enough grip to climb up the 10-inch high vertical side) and the track of the tyre was clear on the baulk, as it gradually veered towards the outer edge, and the two tracks were distinct where the wheels had taken their awful leap into space. The guard rail was smashed down all the way from the point where the car had struck it on entering the bridge to where we had gone over. We discussed the matter of what it was that had caused the car to go out of control and why I could not pull it back after it struck the baulk of timbers. Humfrey said that he was certain the first words I had uttered on emerging from the car were ‘The brakes jammed on” three times repeated. I did not remember it, but the doctor said that, from a psychological point of view, the first words uttered after emerging from a severe crisis are likely to be true even if the shock causes them to be forgotten afterwards. But the brakes had not jammed on because the wheels had not locked. All the way from the place where the tracks swerved to the right long before reaching the bridge until the point where the car went over the side, it was clear that the wheels had been rolling and were at no time locked. Some other explanation must be found. We believed then, and still believe after discussing the whole matter later with various people, that what happened was this.

Obviously the first part of the car to strike the upright of the guardrail when it entered the bridge at an angle was the front bumpers. We had found that the attachment of this heavy stabilizing bumper was the one weak point in the whole car. The method of attaching the bumper to the chassis was not sufficiently rigid to carry the weight of the bumper under the frightful conditions of the surface on which we had been travelling and the bolts had a tendency to come loose. We decided, and have had no reason since to doubt the connectedness of our diagnosis, that when the bumper struck the upright, the bolt broke and the bumper bar itself was smashed back and carried under the mudguard, between the tyre and the mudguard. It wedged there and prevented the wheel from running to the right when I tried to steer the car back towards the middle of the bridge. There can be little doubt that this was the true explanation. Meanwhile the dugout canoe had arrived and Loerand was poled out to the wreck. He decided that before attempting to place it on its wheels, it would be best to empty the car of all its contents as we did not know what damage had been done to the side of the body under water. If it was utterly smashed, all the contents might be left in the bottom of the river when the car was lifted up onto its wheels. Natives crouching on the side of the car, as we had crouched the night before, plunged their arms through the windows and extracted various articles. If we had felt in any mood for humour, it would have been amusing. A native’s arm would dive in and emerge with one gumboot from which he would proceed solemnly to empty the water before putting it in the canoe, or a sodden coat weighing a ton with its load of water appear or perhaps something hideous like an orange or a pot of jam. Almost at once Humfrey’s black bag was extracted, that black bag had held all the money. It was intact, though of course full of water. It seemed to go on for hours, this unloading of the masses of stuff one collects on a journey of this sort. While it was still proceeding, Humfrey told me that when we were leaving to swim ashore, it had flashed through his brain that we might be miles from civilization and need warmth. He had therefore searched in the car and extracted his wife’s favourite rug bought along by accident. Of course, being a thick woollen rug and also being soaked in water, it was enormously heavy, and equally, of course, after swimming 10 yards with it he had to let it go as he was quite unable to support the weight. Actually that rug and an old cap of mine were the only things lost, though our cameras needed some attention, which they got at Nairobi before they would work again and all the cine film, not very much owing to our unwillingness to stop for photographs, but valuable documentary evidence nevertheless, was utterly ruined, also about £30 worth of unused film.

At last the natives announced that the car was empty, and two long ropes were floated out and attached to the front axle. Humfrey tried to persuade Loerand to fasten them to the chassis but without avail. Then about ten natives standing up to their necks in water, pulled the car up till it stood on its four wheels. It immediately sank until the roof was just below water-level: we had fallen as near the edge of the sand bank as that!

Now a great difficulty arose. The car was facing in the wrong direction. It had leaped off the bridge at an angle of perhaps 30 degrees to the line of the bridge and in its fall it had somehow turned completely round through 180 degrees so that it now stood, submerged, with its radiator pointing towards the bridge at the exact angle at which it had left it. In order to pull it out, the front of the car had to be got around through an angle of about 120 degrees. The method adopted was rough and ready, but it worked wonderfully. The natives in the water supported the side of the car to prevent it being pulled over while the villagers, about 150 of them by this time, hauled the front round by man force till it was facing in the right direction. Then every available man, woman and child was put on the two ropes and the car was dragged towards the bank. It was terrible to see our beloved car gradually disappearing under water as the bottom of the river shelved. We felt it would never emerge again. At the deepest part of the channel we could just see the white roof shining through 3 or 4 feet of water. But emerge it did, though every minute we expected the front axle to be pulled right off, for of course we did not know how much damage it had suffered in the crash. It might be now attached to the chassis by only the bolt. If the axle parted or the ropes broke, the car was lost forever, for the water was too deep for there to have been any possibility of getting a fresh rope to it. The axle did not part from the chassis and the ropes did not break and gradually the car began to emerge again, first the roof, then the radiator, and finally the wheels, when the front wheels were almost on the bank, the car stopped with the rear wheels sunk to the hubs in deep white clay. We had also noticed that the front wheels were not turning and the indefatigable Loerand discovered that this was due to the wings being so battered that they were resting on the tyres. A dozen natives, lifting with all their might, managed to tear them clear of the wheels, but still the car would not move, so deeply was the back part sunk in the mud. Humfrey suddenly thought to himself that of course the car was in top gear, so that the wheels were having to turn the engine and pointed this out to Loerand. The latter then told a native in the water to open the door so that he could see. The native did so and picked up something from the floor. Humfrey held it up, “Bertie, your glasses – unbroken!” he called. Something of a miracle that and, though of course I had a spare pair in my suitcase in the car, I was glad to have them back.

During this time, a large part of the prisoners had been set to work by Loerand to make a practicable path up the steep bank from the river to the road. This they did most efficiently, chopping down bushes and cutting away steep shelves of earth, till finally a rough sloping track, winding its way for some 50 yards through the scrub, was made. All hands were then set to the ropes and, giving a series of more or less concerted heaves to the signals of Loerand, the rear wheels freed themselves from the clinging white clay and with a plunge the car stood wholly on dry ground again. Then, laughing and shouting, the whole crowd of perhaps 250 natives, men, women and children, dragged the car up the track the prisoners had cut till finally it stood on the hard-sandy road.

We could then examine it and a sorry mess it looked. The body leaned drunkenly to the left, the side being some six or eight inches out of the vertical: the roof had taken a kind of twist from the deformation; the doors were gaping widely at the bottom: the windscreen had of course completely disappeared – it was made of toughened glass, not triplex sheet. The glass of the window in the rear door had gone and the front near side window out of which we had climbed was broken, with long sharp slivers remaining. The bonnet had been torn bodily away from its fastenings, though fortunately the natives had found it lying on the sandbank beside the car. The front wings were smashed and flattened till they resembled nothing so much as crumpled paper. Both headlamps and one fog lamp had disappeared and the side lamps on the wings were merely flat pieces of chromium plate. Inside the bonnet, the radiator stays were both broken, and the radiator block had been pushed back till the revolving fan had struck it, flattening the tubes. Lying underneath the car we examined the chassis and found serious damage. The rear hanger of the nearside front spring had been torn bodily out of the frame. It was riveted under the frame member and the rivets had not pulled out, but a piece of the steel had been ripped out, leaving the rear end of the spring free. Otherwise there did not appear, to a superficial examination, any vital damage but the tearing out of the spring made it impossible to consider driving the car if it were possible to get it going. It looked terrible, our beautiful car that had appeared so trim and neat, it looked an utter wreck and only fit for the scrap heap.

By this time, it was noon and very hot. We were completely exhausted with standing under the blazing sun and Loerand insisted that we should return with the doctor while he himself would steer the car while it was pushed to the town by the prisoners. We had already made the experiment and found that the front wheels still answered a movement of the steering wheel, so that the steering connections were not broken. Feeling very despondent, we were driven back to the town by the doctor and along to the Post Office, where Humfrey cabled to Thomas and to his wife while I sent a wire to my sister with whom I live. Unfortunately, she was away from home and was horrified to hear on the wireless in the nine o’clock news that night an announcement that we had crashed. It was not until the next day that she received my reassuring cable saying that we were unhurt.

We arrived back at the hospital and feeling very gloomy, we found the car just arriving. Loerand told us that it steered quite all right but we looked at it with feelings of utter hopelessness. It was such a complete wreck. Water poured from it everywhere and we were further dismayed seeing a steady drip of oil from the back axle which seemed to betoken some serious damage there. When Loerand got out of the driving seat, he surveyed rather ruefully the seat of his white duck trousers. Dunlopillo cushions, though exceedingly comfortable to sit on, are not well adapted for immersion in water as they act exactly like a sponge and a large black wet patch showed where Loerand had been sitting. He came in and had a drink with us – our whiskey bottle in the car being still intact – and left for his office after receiving our heart-felt thanks for his efforts on our behalf.

We had lunch and I managed to eat something at last. Over our meal we discussed the future. We ruled out at once any question of being able to go on, a bitter decision but one that seemed to us inevitable under the circumstances, as there were no facilities of any sort for the execution of repairs at Niangara. We decided that the only possible thing to do was somehow to get the car conveyed to Juba, where it could be shipped home by Nile steamer while we ourselves would probably return home by air. We both felt anxious to reach British territory, for there we should at least have the feeling of being among our own people and we proposed to find out if there was any way of getting our car conveyed or towed to Juba, 330 miles away.

We had just finished lunch when a telegram was brought in. It was from Thomas and it put is into a serious quandary. It said “Sorry to hear of the accident. Please cable immediately car total loss. Cable your plans.” It was plain to us that Thomas naturally wished, if the car was lying wrecked in a river, to claim under his insurance policy for the value for which it was insured. But here was the car, though wrecked, standing outside the door and, as I said, it seemed a shame to take it back and push it into the river again. We sent off another cable making the worst of the damage for Thomas to show to the insurance company; but still we were determined that, if it were in any way possible, we would get the car home as salvage, if as nothing else. That afternoon I wrote to Thomas, explaining exactly what had happened. I shall refer to his reply to this letter. We went out to the car, removed the six spark plugs and turned the engine round by hand. It was quite free and as we turned it great jets of water six feet long shot out of each plug holes in turn. We were relieved to see this because we were afraid that as the engine had been running when it entered the water, it might have sucked in water through the carburettors and that the pistons might have been smashed as they came up, water being incompressible. If this had been so, or a connecting rod broken, there would have been no corresponding jet of water from that cylinder when we turned the engine round. So, we were relieved of that fear. When no more water came out, we squirted oil into each plug hole to arrest the savages of rust and replaced the plugs. There was no more we could do, and the engine was not touched again until after we reached Juba, 5 days later.

We stayed at Niangara for four days, meeting with nothing but kindness from everyone. The Administrator gave a cocktail party in our honour and we gave one in return at the hospital where we were kindly permitted to remain, as it was exceedingly comfortable and the food excellent. It was ridiculously cheap: I think we were charged 8/6 a day each including all our meals and medical attention.

Eventually, after some disappointments, we made arrangements with a young Belgian farmer, Lenoire by name, to convey the car and ourselves to Juba, 330 miles away, by lorry. When we asked him how much he would charge, he asked us if 1000 francs would be too much! As this represented about £6.10.0, it struck us as the cheapest form of conveyance we had ever heard of for 660 miles for £6.10.0! Well, well! What would it have cost in England?

“As we drove past the trunks of the mighty trees, strewn asunder and dragged clear by the working party, we decided that if we were ever again caught in a storm in a forest we would stop at the first convenient clearing. Everywhere along the road there were traces of the great storm, trees had fallen in the forest and were leaning against their neighbours, and debris of branches and boughs were scattered far and wide. The road was perfectly dry and the conditions perfect. We were very contented, feeling fit and refreshed after our good night’s sleep. Of course the delay was a nuisance and had upset our schedule completely. Whereas, at the ferry across the River Bibi, some 20 miles before we met the storm, we had been a mere matter of 2 hours 40 minutes late, we were now hopelessly behind. Actually about 16 hours and this meant a complete reorganization of our plans. We decided, however, to do nothing about it until we reached Juba in the British Sudan, about 800 miles further on. There we should be in direct telegraphic communication with Nairobi and could telegraph fresh instructions as to the time we shall arrive there. Meanwhile there was nothing to do except to plod steadily along. Only one thing we would have to do and that would be to send a telegram from Buta, 170 miles ahead, to the Governor of the Southern Sudan at Juba, to inform him of our delay. The reason for this was that we had expected to arrive at Juba in the early hours of tonight, about one in the morning, and he had kindly promised to arrange for the ferry which does not normally cross the river after dark to be waiting for us to take us over to the eastern bank. We could not now hope to arrive at Juba before the next afternoon and we felt that it would only be polite to send a telegram. Actually this telegram was never sent from Buta, because we were told on our arrival there that we should certainly get to Juba before the telegram! As events turned out, it was just as well we did not wire. While we were discussing these matters, we passed through a large native village which seemed, even to our not very interested eyes, to be in an unusual state of alertness. A quarter of a mile on we found the cause. A huge tree, six feet across the trunk, lay squarely across the road, felled by the storm of the previous night.

“As we drove past the trunks of the mighty trees, strewn asunder and dragged clear by the working party, we decided that if we were ever again caught in a storm in a forest we would stop at the first convenient clearing. Everywhere along the road there were traces of the great storm, trees had fallen in the forest and were leaning against their neighbours, and debris of branches and boughs were scattered far and wide. The road was perfectly dry and the conditions perfect. We were very contented, feeling fit and refreshed after our good night’s sleep. Of course the delay was a nuisance and had upset our schedule completely. Whereas, at the ferry across the River Bibi, some 20 miles before we met the storm, we had been a mere matter of 2 hours 40 minutes late, we were now hopelessly behind. Actually about 16 hours and this meant a complete reorganization of our plans. We decided, however, to do nothing about it until we reached Juba in the British Sudan, about 800 miles further on. There we should be in direct telegraphic communication with Nairobi and could telegraph fresh instructions as to the time we shall arrive there. Meanwhile there was nothing to do except to plod steadily along. Only one thing we would have to do and that would be to send a telegram from Buta, 170 miles ahead, to the Governor of the Southern Sudan at Juba, to inform him of our delay. The reason for this was that we had expected to arrive at Juba in the early hours of tonight, about one in the morning, and he had kindly promised to arrange for the ferry which does not normally cross the river after dark to be waiting for us to take us over to the eastern bank. We could not now hope to arrive at Juba before the next afternoon and we felt that it would only be polite to send a telegram. Actually this telegram was never sent from Buta, because we were told on our arrival there that we should certainly get to Juba before the telegram! As events turned out, it was just as well we did not wire. While we were discussing these matters, we passed through a large native village which seemed, even to our not very interested eyes, to be in an unusual state of alertness. A quarter of a mile on we found the cause. A huge tree, six feet across the trunk, lay squarely across the road, felled by the storm of the previous night.